At Home Boston: Healthcare Workers Collection

Boston Book Festival has launched a community writing project to capture this moment in history. We asked residents to send us stories of their experiences during the pandemic, from the acts of kindness by neighbors to the challenges in our biggest hospitals. Many people told us about their experiences as healthcare workers on the front lines fighting COVID-19. The following collection gives us a glimpse into a few of those stories.

To check out more At Home Boston stories, visit BBF’s Facebook and Instagram accounts. We will be sharing submitted stories through the summer.

Originally from Rochester, NY, Vinayak Venkataraman is currently a resident physician in both internal medicine and pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital who finds great joy in the experience of caring for others (and writing about particularly meaningful ones)

This week, I spent my days with patients who wouldn’t wake up. We patted. We prodded. We rubbed. We yelled. “Can you hear me?” Their lungs survived COVID’s rampage. Their ventilators weaned low, their sedation finally shut off. Their minds, however, failed to reignite. It’d take weeks to know if they ever would. Until then, we’d see squints or grimaces. They’re fleeting. We later see nothing.

This week, I spent my afternoons in devastation. Informing sheltered-away families about their lonely loved one’s day. Most weren’t getting better, or worse. They lived in a limbo of sustained slumber, able to breathe but not able to protect their windpipe. Explaining “Trach & PEG” by phone was a daily linguistic and emotional challenge I never want again. One’s sister asked, “Is he suffering?” I didn’t know how to answer.

This weekend, I await the parade of Zoom. One silver lining of COVID has been renewed connection with distant family and friends. They’ll ask how I am. I’ll deflect. I won’t tell about the nightmares, where I’m on the receiving end of those afternoon calls, being updated on them. The thought too grave for my imagination to bear. I wake up, sweating.

Katherine Kilgore is originally from Santa Fe, NM and moved to the Boston area with her partner and her puppy; she is currently a 3rd year psychiatry resident at Massachusetts General Hospital/McLean Hospital

It’s 5 o’clock in the morning. On any other day of any other year, I would awaken begrudgingly to an alarm whose sonorous melody was carefully chosen to peacefully rouse me from my slumber so as to prepare me for what would promise to be another busy day. A day filled with comforting patients, calling concerned family members, collaborating with other clinicians, learning about a new medication.

Today, however, day sixty-five of quarantine, I awaken without such urgency, my mind filled instead with worries about the unborn child nestled deep within my womb, the child I am working tirelessly to protect from the outside world, from the tainted breath of his father, who spends his days caring for those dying from the dreaded virus.

5 o’clock in the morning once meant coaxing my eyes open to a coffee-filtered reality sounding the alarm for the day; today it means awakening to a loud chorus of thoughts, thoughts which have surely raced through the night narrating the anxiety dreams of which I try to make sense. A question echoes, rings through the deepest crevices of my mind and heart: will I be able to keep him safe?

~

Elizabeth Sommers is a public health worker and advocate.

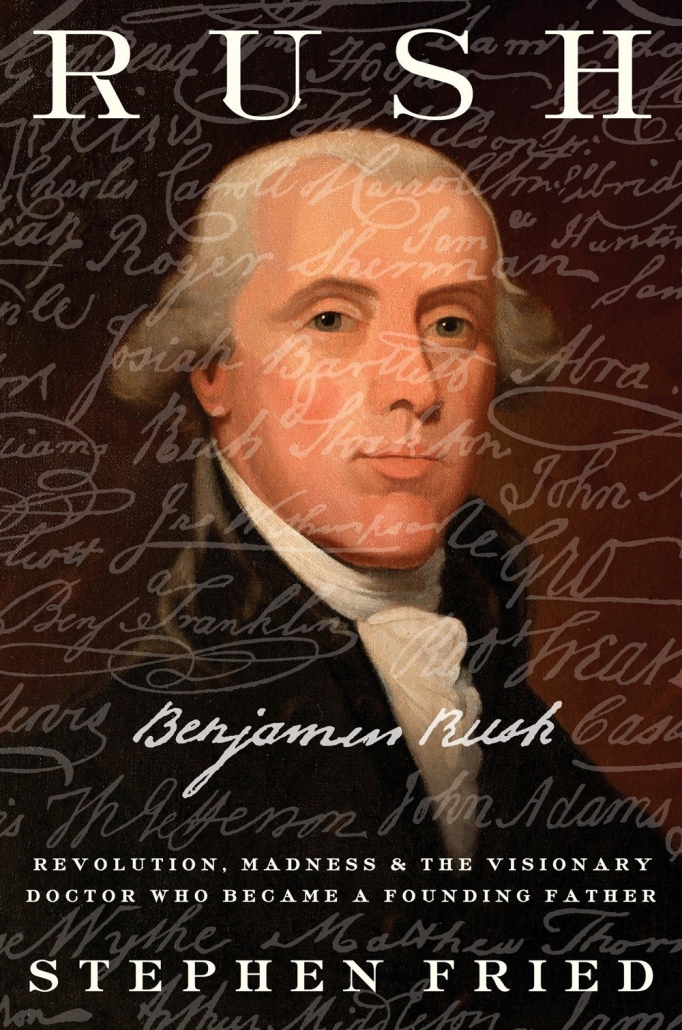

Although I wasn’t consciously seeking to read books about pandemics during my furlough from the hospital where I work, two books made their way to the top of my reading list. “Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush: The Visionary Doctor who became a Founding Father” by Stephen Fried and “The Murmur of Bees”, a novel by Sofia Segovia.

Benjamin Rush, a public health advocate who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, has been called the “American Hippocrates”. During the recurring yellow fever epidemics of the late 18th Century, Rush treated patients in the Philadelphia area. Segovia’s novel is set in rural Mexico and begins with the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918.

It struck me that the same issues of need for physical distancing and temporary isolation, availability of protective equipment and social turmoil were common elements of all three epidemics. Just as temporary isolation is required for safety, it also strains families and communities. The effects of economic insecurity are recurring themes in each epidemic, as is the need to balance societal priorities in times of precarious uncertainty.

~

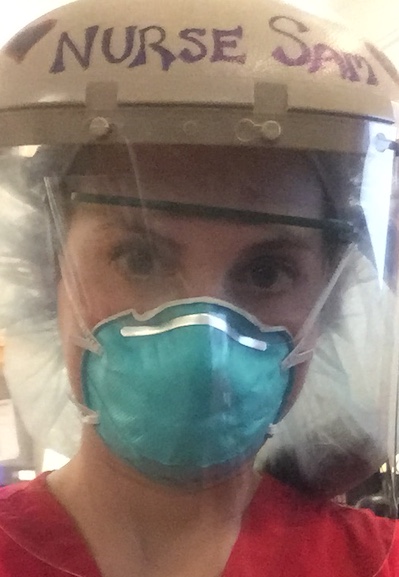

Michelle Heron is a Registered Nurse, Mama, and Yoga teacher

This is the face behind the mask, the face I want my patients to see. The social distancing, shielding, gown, gloves, tight fitting respirator, and mandatory mask wearing for every patient interaction is new world nursing. I have been a caregiver for half of my life, working in hospitals for 22 years. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I have been working as a relief nurse, which means I am floated to where I am needed. Floating is a challenge that requires adaptability, flexibility and courage to face the unknown. My kids are old enough to understand what I do for work and how important nurses are to the health of our communities. They know I work long shifts, overnight shifts, weekends, and holidays. They know I can’t hug them right away when I get home, and they know that meals without me are routine. We connect over video calls, catch up on homeschooling, and they send me love and smiles to cheer me on. I don’t know what the future of my nursing career holds, but I do know that nursing has always been a practice of hope, support, strengthening, caring and empowering others.

~

Samantha Fabian is a COVID Nurse

I am a nurse caring for patients with COVID-19. My unit was turned into to a COVID-19 dedicated unit when the storm raged in. I am also a mother to two babies.

I sit in the parking lot before my shift and I cry. I write my feelings down as an outlet and therapeutic tool. I need people to hear me. I want to scream at the top of my lungs for people to understand how hurtful it is to watch people not social distance while I sit with my patient as she cries and struggles to breathe after she watched her husband succumb to COVID-19, and now it is her turn to fight.

I want to pray. I want to cry. I want to do anything I can to make this better. What I do is go into work and care for patients. I nurse the hardest and bravest I ever have in my life.

I also need people to know I suffocate. I have to wear a tight-fitting mask that I cannot remove for hours at a time. Sometimes we are only allowed one. And now our masks will be sent off to be decontaminated, they tell us. They will be sprayed with chemicals and given back to wear over and over. We used to throw these masks out after we left each patients’ room. Every single time. I feel like we are being poisoned. By our own carbon dioxide. By our PPE.

Yet l feel lucky enough to even have something to protect me. I feel betrayed. How can this be real? How can we be doing “God’s work,” the most noble profession, but be treated this way. I make the choice to leave my family and be a nurse. Be brave for the ones who need me. I will save a life and, sadly, I will comfort as a life is lost. I am fiercely committed to my patients, as all nurses are. That is why we are putting our health on the line.

But we are worth more. Our lives and our safety are worth more than this. Please stand by us. Please help us by doing your part and staying home. And hear us. We are suffocating.

From a sad nurse.

~

Stephanie Collier is a psychiatrist at McLean Hospital.

I work with vulnerable older adult patients with medical complexity and mental illness. I also work with trainees in psychiatry who are demographically classified as lower risk. Although I worry about everyone’s safety, I worry most about the people with hidden risk factors.

We do not know whether the virus itself or the consequences of the pandemic will harm people with mental illnesses more. Similarly, we do not know whether the virus itself or the consequences of the pandemic will harm young doctors more. Although we have models illustrating how social distancing saves the lives of vulnerable older adults, we also understand that social distancing increases the neglected outcomes of malnutrition, child abuse, and domestic violence. We do not know the effects of isolation on vulnerable individuals, just as we do not know the effects of going into work on vulnerable individuals.

We do know that there is great heterogeneity within these groups and that staying at home, or going into work during an epidemic, will have profound effects on the mental health of individuals. This suffering will often remain hidden until a life is lost to suicide or illness.

~

Amrapali Maitra is a resident physician in Internal Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an anthropologist.

I often revisit the scene in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things where Ammu and Velutha meet at the riverbank. The Big Things are overwhelming—the caste differences that forbid their love—so they focus on Small Things. An insect has built a home out of rubbish and leaves. They tend to minutiae like life depends on it.

The pandemic is a study in Small Things. On a walk, I hear a blue jay’s liquid screech. Enjoy fuchsia eruptions of rhododendrons in the Arboretum. Inhale ash from my neighbor’s backyard, conjuring nights of s’mores and songs. Spy a family of squirrels relocate to the rain gutter.

COVID has transformed my identity as a doctor. In March, I cared for cancer patients. But while pregnant, every moment in the hospital became a negotiation between duty to others and obligation to the life inside me. So, I transitioned to virtual care.

Sitting at my dining table, I begin each phonecall, “This is Dr. Maitra! How are you coping?” The words are chalky in my mouth. I swallow the guilt. Sheltering in place, I’m no hero. Then I feel my daughter’s forceful kicks and realize, I’m exactly where I need to be.

~

Jane deLima Thomas is a palliative care doctor at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

My father had a massive stroke on April 13th. My mother called me and said, “If you want to see him, you should come now.” Without thinking about COVID or my mother’s fragile immune system, I leaped into the car and drove to their home. I looked down at the man who had raised me and I scanned his face and hands, committing them to memory. I told him I loved him and I believe he mumbled that he loved me, too.

I am a palliative care doctor, and during the pandemic I’ve had to call families and tell them they couldn’t come to the hospital to see their dying loved ones. I have withstood their anger, tears, and begging, knowing it was safest for everyone – patients, staff, and families themselves – if they stayed away. I did my best to be compassionate, but it wasn’t until I felt the primal need to see my father one last time that I truly understood the terrible loss families experience when they are denied the same. And now I feel the heaviness of it deep in my chest every time I reach for the phone to make another call.

~

Katherina Thomas Medical case manager, medical humanities practitioner and researcher on epidemics

On a night shift caring for Covid-19 patients in May, I found a flock of origami birds that someone—a colleague, or perhaps a patient—had made. The hospital was quiet, most patients asleep, and so I sat arranging the birds as one of the hospital cleaners walked by. I’d come to admire them, these huge guys in double respirator masks and industrial gear, risking so much for such little recognition. What drove them, I wondered. Was their work also a form of love, like ours?

One of them came over. He cradled a delicate bird in his double-gloved palm, and in Spanish he called his colleague over. They towered over me, they held the swans so tenderly. And although we’d never really seen each others’ faces, for a moment we were no longer under fluorescent lights and layers of plastic, but outside, in nature, with friends. Afterwards, as the cleaners walked away, I grabbed a pen. I wrote LOVE IS POWER on the wings of one of the birds, and I went back to work.

Joanne Cassell is a mother, nurse, patient advocate and life long student.

Who are the Real Heroes?

They are calling me a superhero but I don’t feel like one. The superheroes are the people fighting for their lives. Like the psychotic person keep alone in isolation at a time when he needs counseling and group therapy or the person who is dying and the family has to talk to them by phone or the patient who just got extubated and her son is still intubated in the next room.

Before I go to work in the morning I have to make sure I eat and drink something otherwise there is just not enough time. Caring for Covid-19 patients is physically and emotionally challenging. Wearing an N95 mask, the suits and shields all day is a nightmare. I often get overheated, my throat gets dry and I become lightheaded from sweating and breathing in my own CO2.

Finally, when I get home I don’t recognize myself in the mirror. My face is marked and aged from wearing a mask for twelve hours and my body weak from the long day. I take a hot shower wishing for peace and quiet – no beeps, or phone calls. I mindlessly watch TV and cuddle the dogs. I struggle to get some sleep, but it often evades me because I am filled with guilt and fear that I could have done more.

Read more about BBF’s At Home Boston community writing project, in partnership with the Boston Globe.

Follow Boston Book Festiva’s At Home Boston project on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Share these stories using the hashtag #athomeboston.

Read more At Home Boston stories: