At Home Boston: Dropped Connection and Other Essays

Boston Book Festival has launched a community writing project to capture this moment in history. We asked residents to send us stories of their experiences during the pandemic, from the acts of kindness by neighbors to the challenges in our biggest hospitals. We wanted to hear it all from all corners of the city. The following is the first selection of stories selected to be featured in the Boston Globe, our media partner in this project. Submissions will be accepted through June 30, 2020.

Last night, my husband cooked lasagna. I took out the trash. There’s something simple about living at home together, being there for each other. Before, I think we both lived on our own.

The Stranger

I’ll never forget her calm voice as she explained that my husband had been in a bicycle accident. A stranger who had stopped to help, she must have known it could risk her life. She passed my husband’s phone to a police officer, who told me the ambulance was heading to Mass. General, “the closest hospital with a trauma unit accepting patients.” When she took the phone back, the stranger told me my husband was conscious, but not walking. I asked for her name.

No visitors were allowed at the ER. It took hours to learn the extent of his injuries: seven cracks in his ribs, torn ligaments in his shoulder, but no damage to his head, neck, or back. He’d tucked and rolled flying over the handlebars after a pickup truck took a right turn in front of him. He was wearing a good helmet.

Because of potential exposure, my husband recovered while quarantined in one room of our house. Four weeks later, I was laid off. We’ll be fine. My husband can walk.

I found her online; I wanted to thank her. She said knowing my husband was OK was the only thanks she needed.

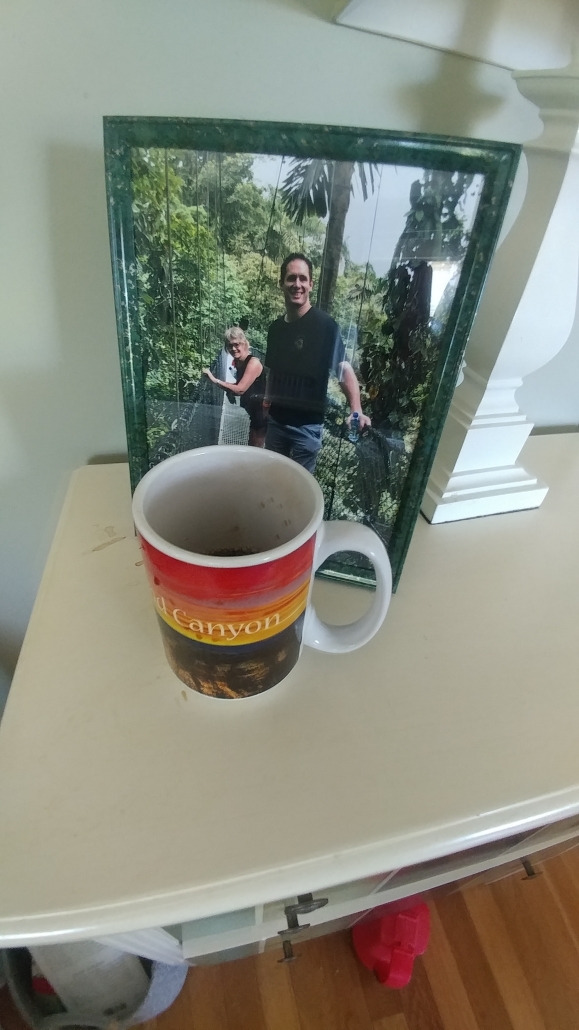

My alarm rings at 5:30 a.m., in keeping with my efforts to maintain a regular schedule. I sip strong black coffee in the oversized Grand Canyon mug that my son gave me years ago.

He died last summer of a sudden heart attack at the age of 33, three months before his wedding. There were zero warnings. He was so healthy. I start each day trying to capture some of his endless kindness, encouragement, and optimism. I want to bottle his spirit and open the cap when isolation overcomes me.

How different it would have been if he had died this year. I tear up for all who lost loved ones and could not say goodbye, could not have visitors and hugs. The hugs I would have missed the most.

The grief tsunami still washes over me most days, but I also remember the love that enveloped me and my daughter; the many family and friends who cried with us. I remember the walks and coffee with friends who kept reaching out when I retreated. I mourn each day, but am grateful that he did not die alone. And that I did not grieve alone.

Comfort and Love in a Single Word

As I’m running out to do last-minute errands before the lockdown, my daughter calls from Texas.

“What’s up?” I ask.

“Just checking in on you.”

“Why? You worried about me?”

“Well, you’re in the high risk category, you live alone, you are my mother, and I love you. And, yes, I need to know that you’re okay.” At that moment, I realized how the pandemic has pushed my generation through a premature reversal of parent-child roles. And while I didn’t want to add to my daughter’s coronavirus fears, my independent streak did not want a daily check-in call.

A conundrum to be sure, but here is our inventive solution. Each day I do the Spelling Bee, a highly addictive, seven-letter anagram challenge on the NY Times app. The big prize is finding the pangram, a word that uses all seven letters. Each day I text my daughter the pangram as a sign that I’m still okay.

My days roll by in these sheltered times, each one marked by its pangram: parkland, bewitch, artfully, genotype, adjunct, compound, outgrown, implicitly. A daily text with a single word may seem nonsensical, but for us it says everything we need to know.

Dropped Connection

I met Tyrell in December, in the big echo-y corridor of a Boston high school. His teacher introduced us, telling me he was a “sweet” kid who was struggling with his writing. I felt the sweetness right away.

Then came the struggle. His first assignment was to write a review about a rapper. I felt his powerful admiration, not for the music or poetry, but for the aura of success, the designer accessories, the fame. This all came out in warm monosyllables. I asked follow-up questions, and as he searched for words, I would say, ”That’s good. Write that down.” Once, our work abruptly stopped as he told me about his mother’s death when he was nine. He went silent for a long minute. When I asked, he said, “No, it’s all right.” We went on.

As our last session ended I said, “I’ll see you in March.” When March came, I had a persistent Covid-like dry cough, and by the time it resolved, schools were closed. I wrote to Tyrell’s teacher, asking if I could still work with him online, but her reply was tinged with sadness. He had slipped away from her, from school altogether, in the transition.

~

Tell us your story about these unprecedented times in less than 200 words. Read more about BBF’s At Home Boston community writing project, in partnership with the Boston Globe.

Follow Boston Book Festiva’s At Home Boston project on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Share these stories using the hashtag #athomeboston.

Read more At Home Boston stories: